When the 15 hour week looked possible

Explaining the incredible shortening of the workweek from 1910 to 1940

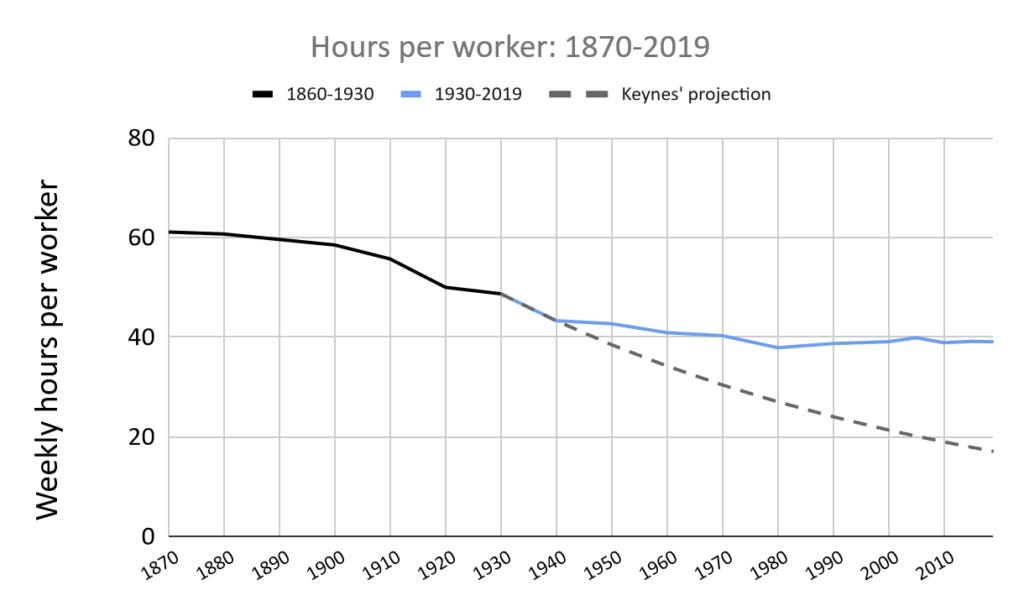

Between 1910 and 1940, the length of the workweek dropped an astounding 12.4 hours or 22%, from 55.7 to 43.3. Had this pace continued, we would not be far off from John Manyard Keynes' projection of 15 hours weeks by the year 2030. How did this trend start, and why did it stop?

A broad overiew

Robert Whaples of Wake Forest University (who compiled many of the numbers used here) explores some of the unique circumstances of 1910-1940 in his analysis of Hours of Work in U.S. History. He noted that there was an unprecedented 18% increase in wages between 1914 and 1919 alone, and that many workers used this increase to "buy" some free time back. These shortened hours were increasingly codified into law: in 1916, Adamson's Act was passed, which guaranteed all rail workers an 8 hour day.

Sometimes, changes happen slowly, and then all at once. This certainly seems to be the case with the workweek in the early 20th century. The slow shifts of both children and seniors out of the workforce in the 1900s, combined with the localized efforts of organized labor from 1886 onward all of the sudden met the surge in wartime demand, accommodating monetary policy1 from the newly established Federal Reserve, and a sharp decrease in immigration. The shock of the war gave workers a lot more bargaining power, and the shortening workweek created a positive feedback loop.

These trends continued into the 1920s. Precedent was set for more regulation of labor conditions, and new immigration laws kept the number of new arrivals near their wartime lows. Demand remained high as new products like radios and automobiles replaced wartime consumption— after a postwar recession, economic growth continued to accelerate. The strong bargaining position of workers in the 1920s brought the workweek down to 5 days from 6. The Ford motor company was at the forefront of these changes— they were one of the earlier companies to adopt a five day workweek in 1926 after also being ahead of the curve on raising wages to over double the prevailing rate in 1914.

Even as demand evaporated during the Great Depression, companies were still encouraged to reduce hours. A bill mandating a 30 hour week nearly passed Congress in 1933, but a law guaranteeing union organization was passed as a compromise instead. Membership in unions increased substantially and the workweek sustained its Depression-era decline even as the economy picked back up.

Diving deeper

The keeping of economic statistics in the modern sense was still only in its infancy during this era, so it’s hard to make a case for any particular factor contributing a specific percentage to the increased bargaining power of workers or the drop in working hours, but it can still be instructive to take a closer look into each of the major shifts.

Policy

With World War I as the prime catalyst for the surge in demand and crop prices that improved labor’s bargaining position, public policy (both fiscal and monetary) was arguably the most significant factor in the decline in the workweek. The massive mobilization that came with the U.S. entry into the war in 1917 was only made possible by two new authorities which had only come into existence four years earlier:

The Sixteenth Amendment, which granted the federal government the ability to levy an income tax, and whose support in state legislatures surprised its proponents at the time.

The Federal Reserve System, whose ability to purchase government bonds was used extensively during the war to cover revenues that the government couldn’t raise through increased taxation alone. The introduction of Federal Reserve Notes in 1915 (the paper money that we still use today) roughly tripled the nominal supply of money by 1919.

This increase in the supply of money and corresponding inflation, was the beginning of the end of the era of financial panics like the Panic of 1873, and set the stage for the Keynesian economic policies of the 1930s. The Great Depression was the final straw for the gold standard, as the increased demand for currency in a world where economic and population growth far outstripped gold production made maintaining it in hard terms increasingly untenable. If the scarcity of gold made hoarding it more profitable than more “productive” investments that both increased the demand for labor and improved the standard of living (as had been the case during the many financial panics between 1870 and 1930), how would society advance? The appeal of centrally-planned economies in this era is understandable in light of the tensions caused by the gold standard.

The stronger position of workers, both before, during, and after the Great Depression shifted the Overton window on other labor laws. Whereas the otherwise progressive Teddy Roosevelt in 1903 felt that the federal government did not have the authority to restrict child labor, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 largely outlawed it along with introducing the first federal minimum wage among other provisions, and was passed with overwhelming support.

Technology

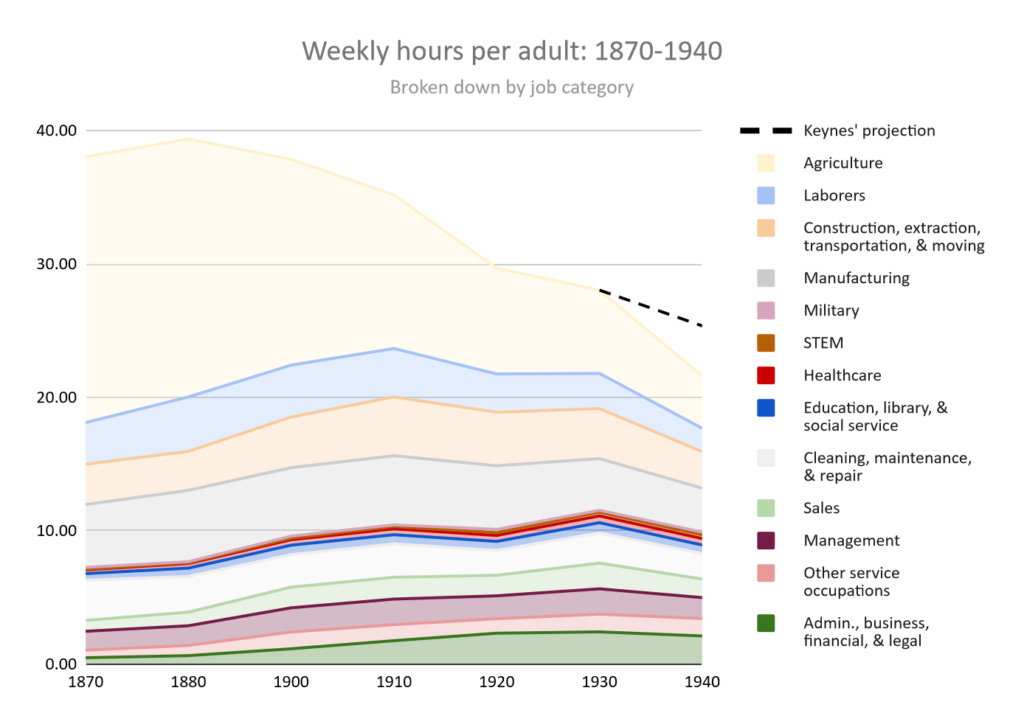

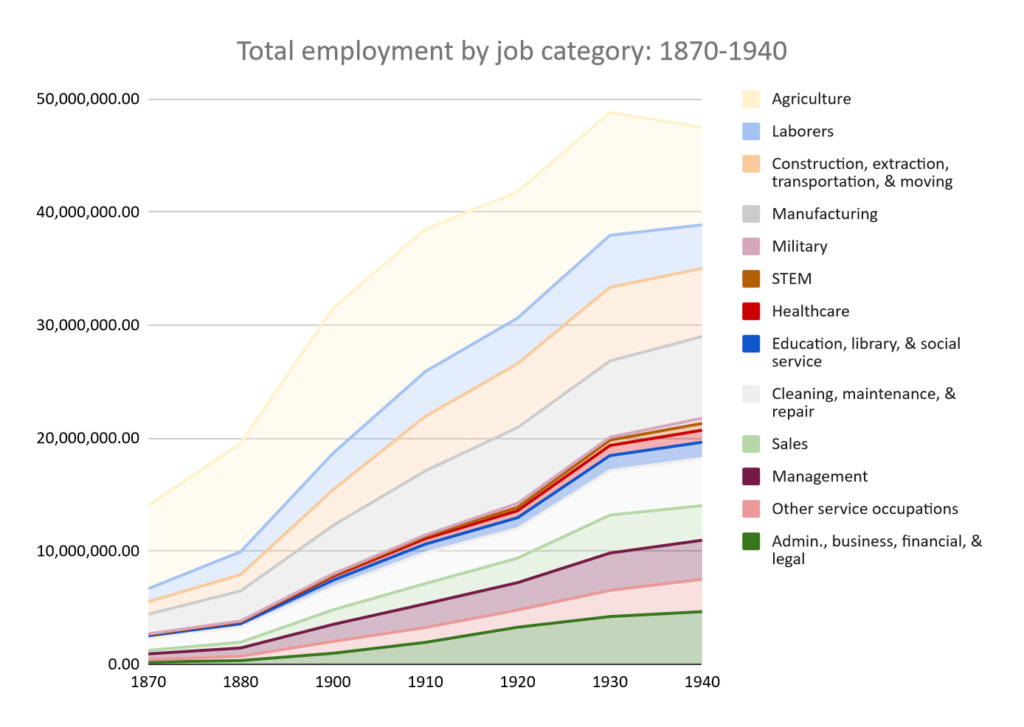

Technology was likely the second biggest driver of the shorter workweek. We can take a closer look at what types of jobs people were working to see where change was being felt the most:

The most notable drop we see is in agriculture, which constitutes over half of the decline in work from 1910 to 1940. Manufacturing, construction, and general labor hours constituted most of the remainder. Urbanization and the mechanization of agriculture makes the decline in farm work no great surprise, but that there is an overall drop in manufacturing hours worked seem uncharacteristic of an era of increased industrialization. But the same forces that advanced agriculture— the increased harnessing of fossil fuel energy2 — brought the electrification of factories, which combined with innovations in chemistry and telecommunications led to a record 5% total factor productivity growth in manufacturing every year in the 1920s, allowing work hours to decrease while output and wages still went up.

The unique nature of agriculture in the U.S. may have also indirectly increased the bargaining power of workers. Farmers, unlike factory workers and most other laborers, often owned their land and equipment, and benefited much more directly from commodity price increases like those that happened between 1917 and 1920, and the technological improvements that became available to them during this period. While immigration from abroad (of primarily landless Europeans) contributed substantially to population growth in cities between 1890 and 1910, when World War I started and later restrictions on immigration were passed, employers in cities would have to raise wages substantially to attract landowning farmers in the U.S., though falling food prices forced some farmers off their land in the 1930s.

Demographics

While the percentage of Americans doing farm work decreased dramatically between 1870 and 1930, the absolute number of farmers was surprisingly constant— this same population was just supporting an even larger increase in the population in cities.

As immigration declined in the 1910s, internal migration rose. There was one rural population in the U.S. who were disproportionately non-landowners: African Americans who moved north during the Great Migration. Had reparations after the Civil War made the distribution of land more equitable, one can only imagine how much power labor might have had during this time.

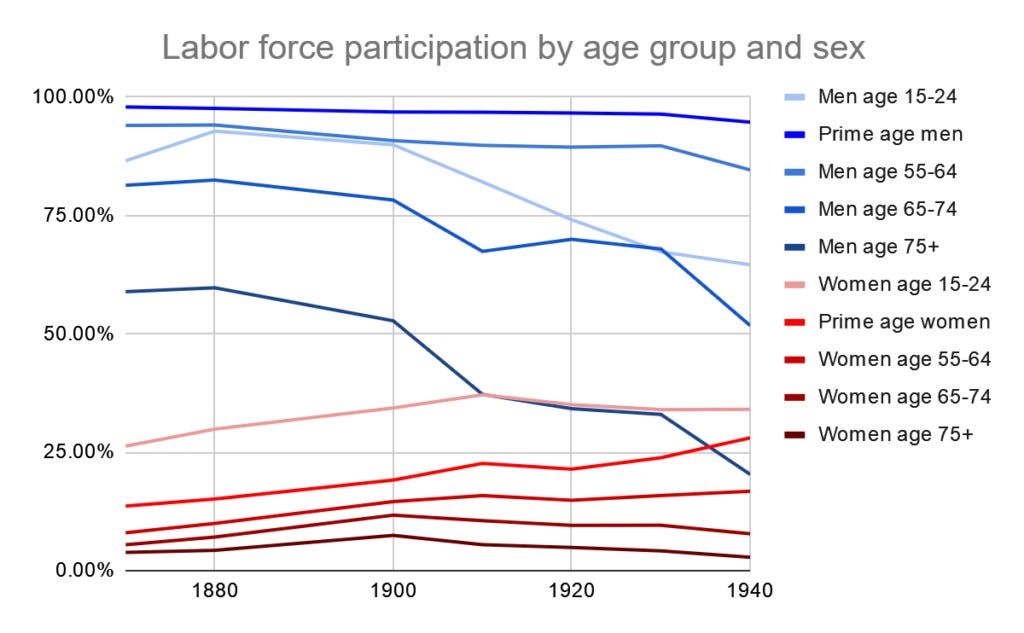

Nevertheless, there was still some demographic pressure on the labor market similar to the previous era. Like the effect of Civil War pensions in 1907, the establishment of Social Security allowed roughly a million more people over age 65 (around 2% of the labor force overall) to to retire earlier than they might have otherwise.

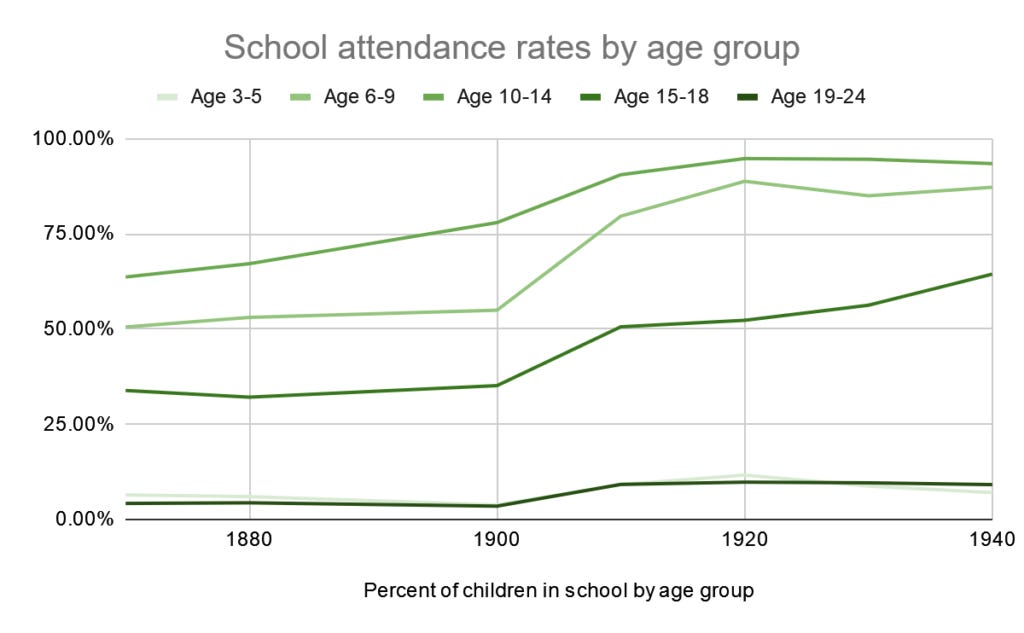

Reflecting how difficult it was to get a job with no experience during the Great Depression, we see a significant decline in labor force participation among young men going into the 1930s (participation among young women declined only slightly, but was already at a lower level). There is a corresponding increase in these young people attending high school:

Culture

In light of the significant geopolitical, technological, and demographic shifts of this era, culture seems like it was largely downstream from these other changes. Yet it was still a decisive factor— workers still chose to use their newfound bargaining power to get more free time back, which was a self-reinforcing cycle. Voters generally continued to choose leaders who favored a larger role for the federal government, whose policies largely increased the power of workers in this era. And there were many more voters making these choices in 1940 than there were in 1910, as the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteed women the right to vote in 1920. Pioneers like Jeanette Rankin and Frances Perkins, the first female members of Congress and Cabinet respectively, inspired a new generation of women to seek similar opportunities.

Similar choices would present themselves for the next generation. But what would they decide?

Continue reading Part II: So why aren't we down to 17 hour workweeks in 2022?

This policy took the form of bond issues and roughly tripling the pre-war money supply in the form of Federal Reserve Notes, the same currency we use today.

Vaclav Smil’s Energy and Civilization: A History is a fascinating deep dive into the technological advancements in both agriculture and industry over time.