What if 15 hour weeks were only 9 years away?

The pitfalls of predicting the future of work 100 years out

As I continue to ponder what everyday life 100 years from now might look like in my comic 2120 Hindsight, the future of work looms front and center in my mind. Work drives culture in many ways, and enjoying a sabbatical from paid work myself has driven me to reflect more on this.

Will increased automation and productivity bring about a world where leisure is more central to life, or a dystopian race to the bottom where people compete over a shrinking pool of possible ways to earn a living? Or are these predictions, both optimistic and pessimistic overblown? Part of wrestling with these questions has led me to think more about people in the distant past who predicted our present, and what they got right and wrong.

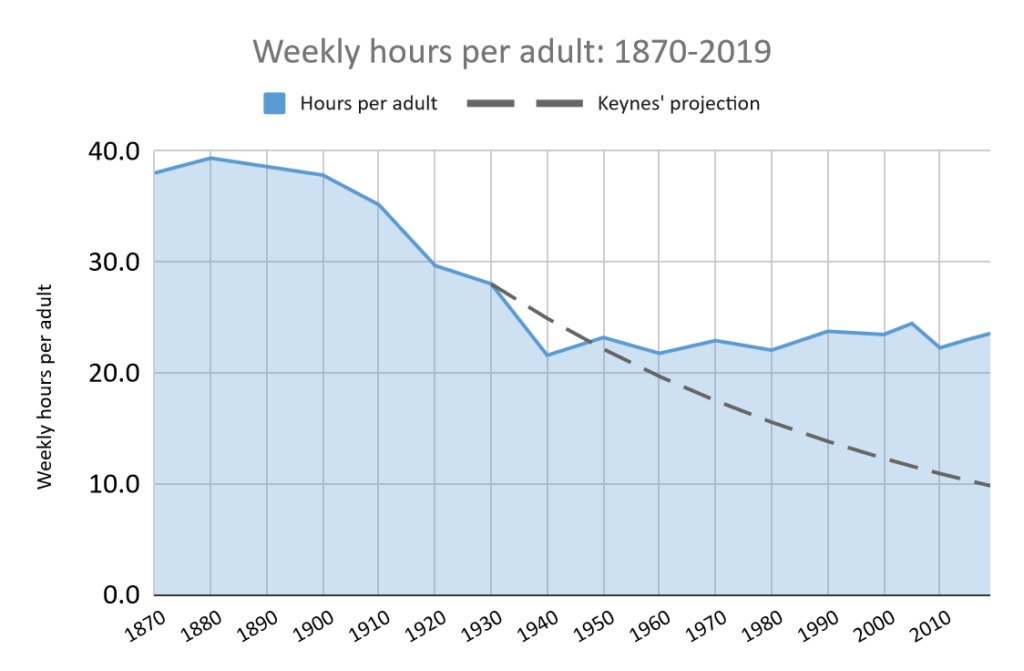

In his 1930 work Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, John Manyard Keynes speculated that in 100 years the average person might only work 15 hours per week. Barring some dramatic shifts over the next 9 years, this is looking pretty unlikely. There are many theories as to why, and a lot we can learn from some of the details that Keynes missed. Let's look at the numbers.

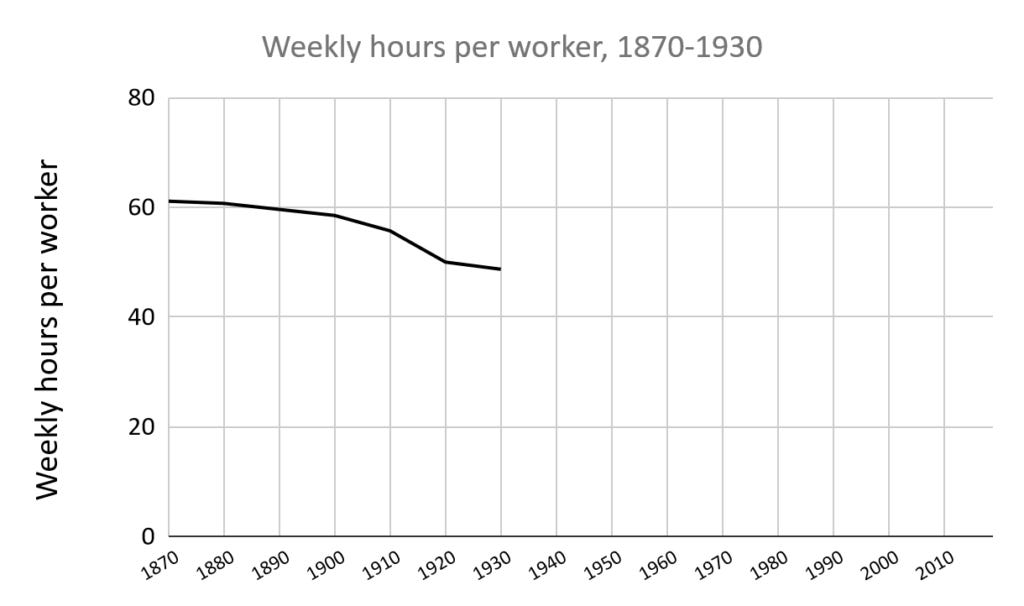

While data prior to the 1940s isn't fully representative of the population, some general trends can be observed from various surveys that were done in earlier times. In the U.S. in 1929, the average working man clocked 48.7 hours per week, which was a significant reduction from the 60+ hour weeks workers averaged in the late 19th century. Where else could we go but down?

Keynes was roughly right for the first 10 years, and not too far off even as late as 1980 when weekly hours hit a low of 37.9. But they have plateaued ever since.

Only looking at the usual weekly hours per worker hides an even more significant trend: there are many more women in the workforce than in 1930. The labor force participation rate captures this, as it counts overall what percentage of the non-institutionalized population age 16+ is currently working or actively looking for work. For women, this rate rose from 25% in 1930 to 59% in 2005, nearly catching up with men, which fell from 87% to 73%. In theory, more people working should mean fewer hours for everyone, but as we’ll explore later, this doesn't work in practice. Taking this into account, the total amount of paid work being done per adult has actually increased since 1940.

1Notes on methodology, caveats below.

We can effectively divide Americans’ perception of the workweek into three different eras, and a prediction for the future:

1940-present: The incredibly stagnant modern workweek: A 5-part series exploring different themes

Would you rather have more free time or more stuff? And when do workers have a choice?

Is the government keeping the workweek long? How has policy has explicitly and implicitly influenced the length of the workweek?

How much more productivity would we actually need to get to a 15 hour workweek?

Do Millennials really not want to work anymore? How much do generational differences really affect the length of the workweek?

A tentative prediction for the workweek in the year 2120: looking at the global relationship between economic growth, working hours and productivity.

Weekly hours from Weeks report, Owen's survey, and Census multiplied by the number of workers counted by select Census samples available in IPUMS USA, plus author’s adjustments accounting for under-counted child laborers, unpaid family farm labor, and military service members. These adjustments are detailed more in the footnotes here.

Note: non-farm hours from earlier surveys may be somewhat overestimated because only men's hours were measured before 1940. Women's non-farm hours were believed to be about 6 less than men's on average, but on the other hand, the farm labor of women is likely underestimated.

Starting in 1940, the employment status of workers was also tracked. The hours per adult estimates prior to 1940 may be somewhat high as they include workers who reported an occupation but were actually unemployed at the time. These individuals are excluded from the hours per adult estimate starting in 1940 to give a more accurate representation of the overall hours actually spent working.