How many people make a living from music?

All of your questions answered in 8 charts

As late as 2015, it was commonly believed that creative jobs were very safe from automation. But just four years later, there were already signs that generative tools might be capable of creating some of the AI music we are familiar with in 2024. Does that mean we will see many musicians and other artists out of a job soon?

These worries actually go back much further than most people realize. We see fears about jobs (and intellectual property rights of artists) going all the way back to the invention of recorded music. Why go out and see a live show when you can listen to all the hits of the day in the comfort of your own home on your Edison Phonograph?

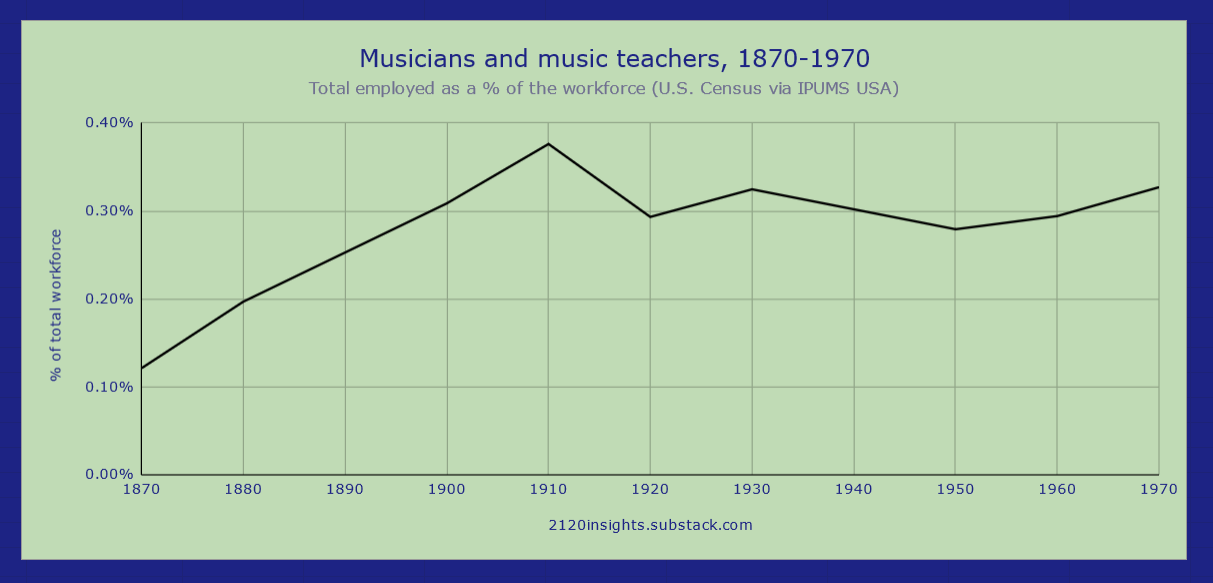

Indeed, the number of musicians dropped by nearly 25% over the 1910s when this cartoon was published. In addition to the explosion of record sales, Prohibition and cabaret taxes further devastated the live music industry, which by 1920 was bouncing back from the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918.

Recording and transmission technology advanced even more in the 1920s. Improvements in sound quality led to musicians losing jobs in theaters when “talkies” first hit the scene in 1927, and radio allowed an even cheaper medium for access to a greater variety of music in ways the foreshadowed the impact of digitization and streaming nearly a century later. But in spite of these developments, the Census shows that most of these musicians were still able to make a living, as the total number actually started to grow again.

What can we learn from the last time we were in the 20s and technology was rapidly reshaping the music industry? Several factors might have helped the musicians of that era:

The increased diffusion and popularity of a variety of musical styles (notably jazz)

More economic prosperity and leisure time enjoyed by workers

Bold actions taken by the American Federation of Musicians (AFM)

Technology has continued to evolve, and the revenue made from recorded music has fluctuated significantly with economic conditions and the ever-changing form factors.

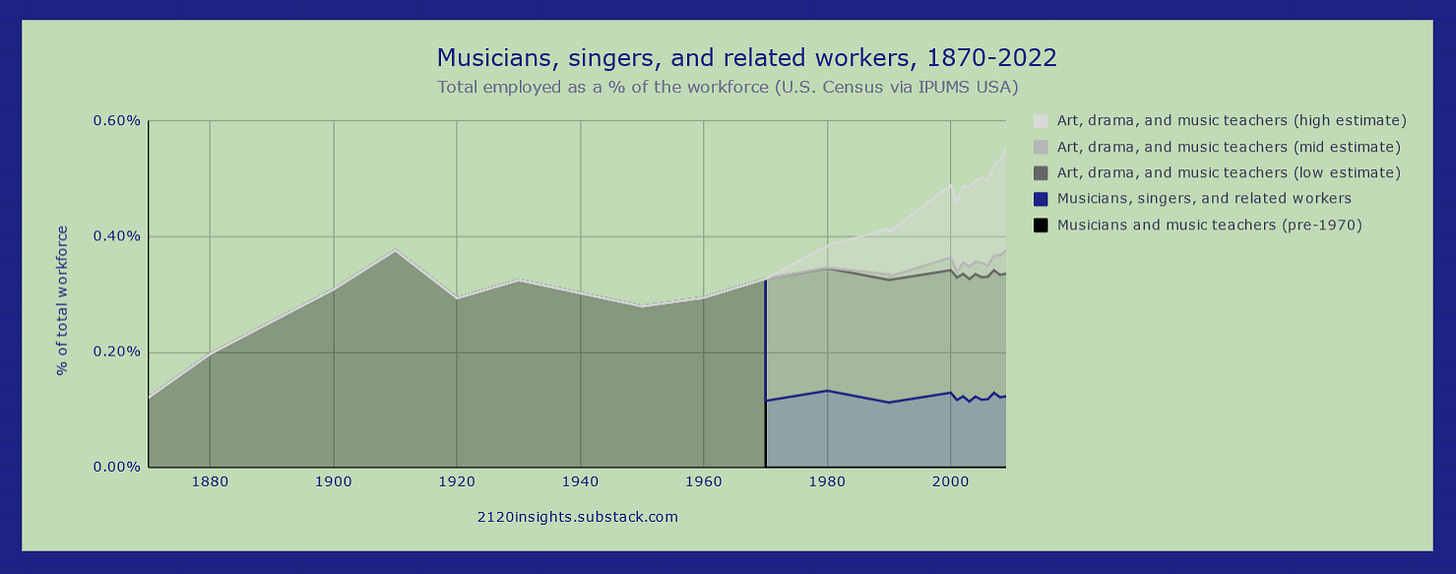

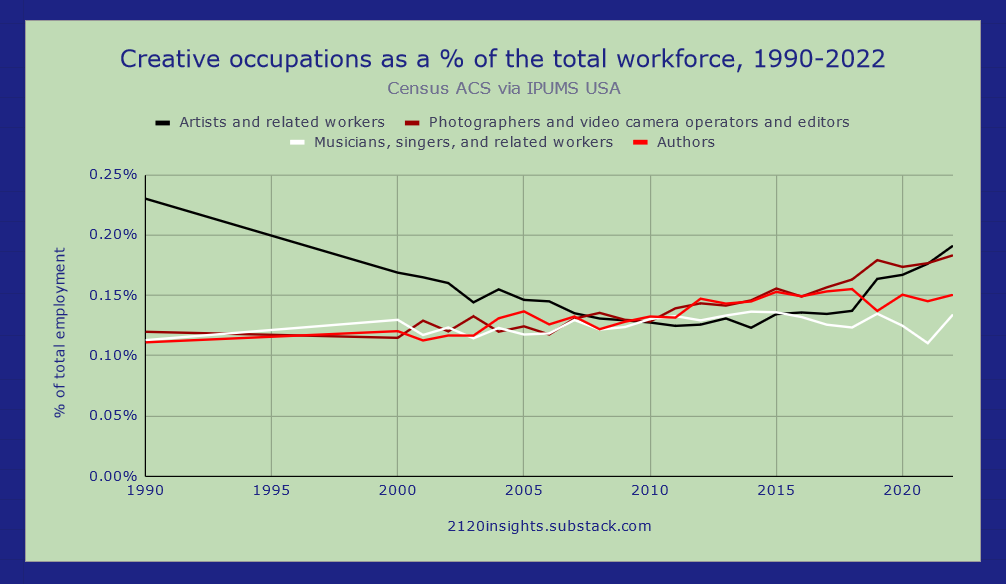

But the percent of the workforce that makes a living from music has remained remarkably steady ever since: about 1 in 750 workers, or 1 in 200-3001 if you include art, drama, and music teachers, who were counted in the Census occupation “Musicians and music teachers” prior to 19702.

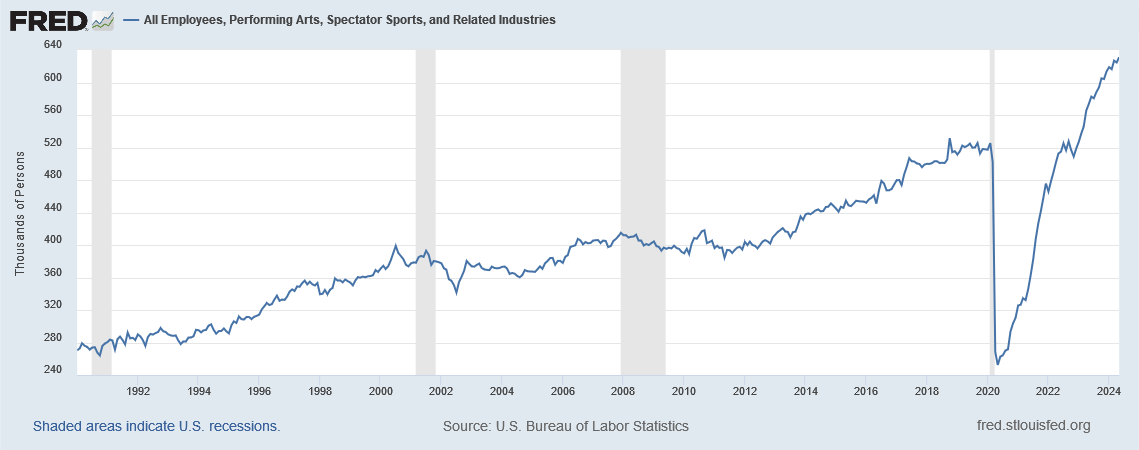

It’s worth noting that the above chart only goes up to 2022. Looking more generally at jobs in the performing arts, spectator sports, and related industries (which also includes the many other types of professionals needed to put on shows), we see over 100,000 more jobs— a 20% jump— in the 16 months between January 2023 and May 2024 alone. This unprecedented increase in interest in live events, which had already fully recovered from the pandemic by early 2023, has even been identified as a significant contributor to inflation.

What takeaways from the past are still relevant today?

There are some notable similarities and differences between the 1920s and 2020s. Like the first diffusion of records in the early jazz era, streaming has exposed people to a greater variety of music than ever before. Between younger people preferring experiences over things and shorter working hours than previous generations, as well as a burgeoning population of retirees getting out to enjoy events like “Geezer Happy Hour”, there is more free time available to get out and have fun.

On the other hand, old music is an increasingly large share of what people listen to; a trend that’s likely to continue with an aging population. This might make it harder for new artists to gain traction, but the internet-accelerated trend of micro-culture over mass culture helps support a broader base of artists too. But does micro-culture make it harder to unionize? Although the number of musicians has grown with the population, membership in the AFM fell through the 2010s and in 2024 is less than half of what it was 100 years before.

The bottom line

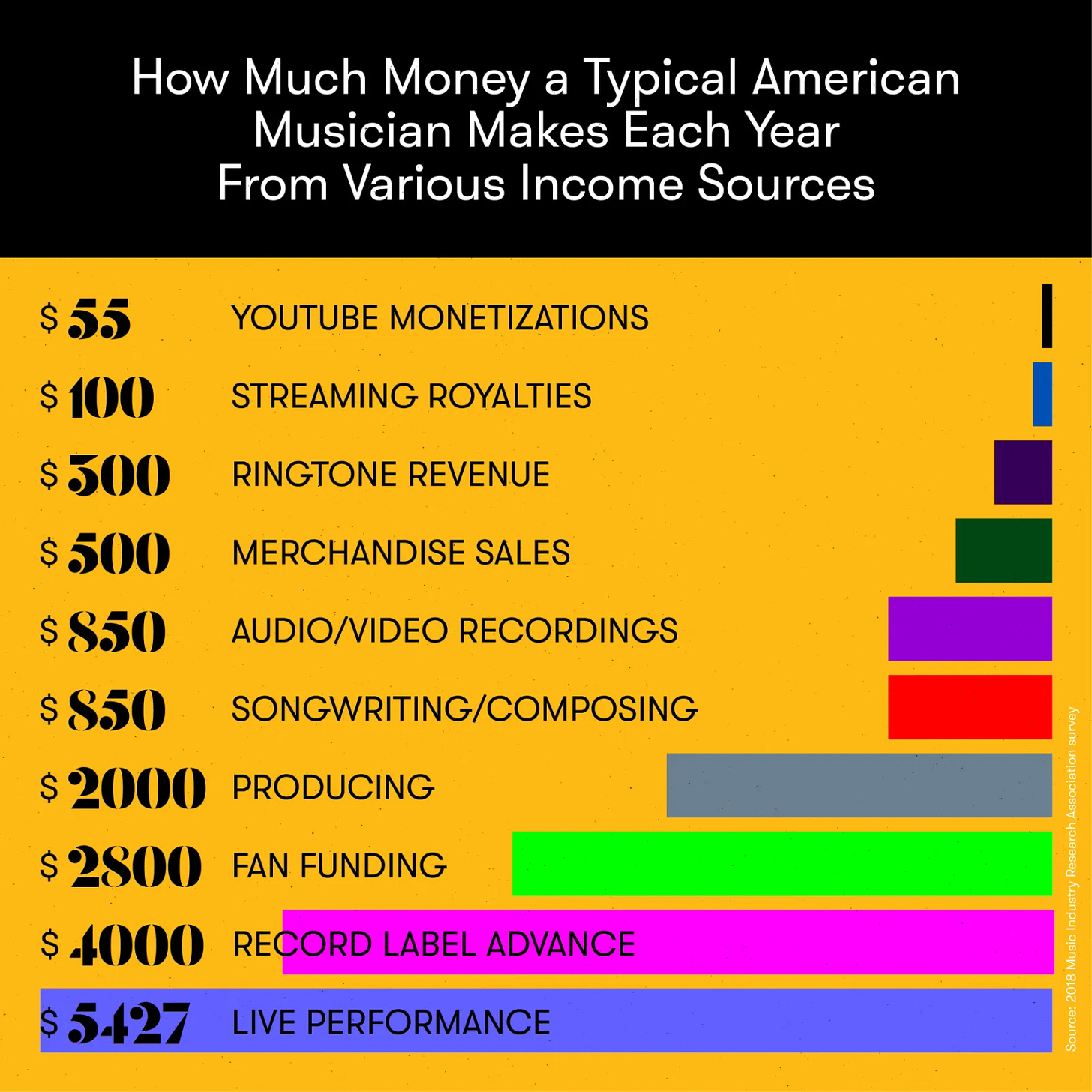

While advances in AI could threaten artists’ income made from recorded music, it might also complement human creativity and lead to new styles similar to how photography influenced the development of impressionist art. Fundamentally, it seems unlikely to depress turnout at live shows in the way the phonograph did in the 1910s. And income from shows (along with merchandise) comprise the lion’s share of most musicians’ income.

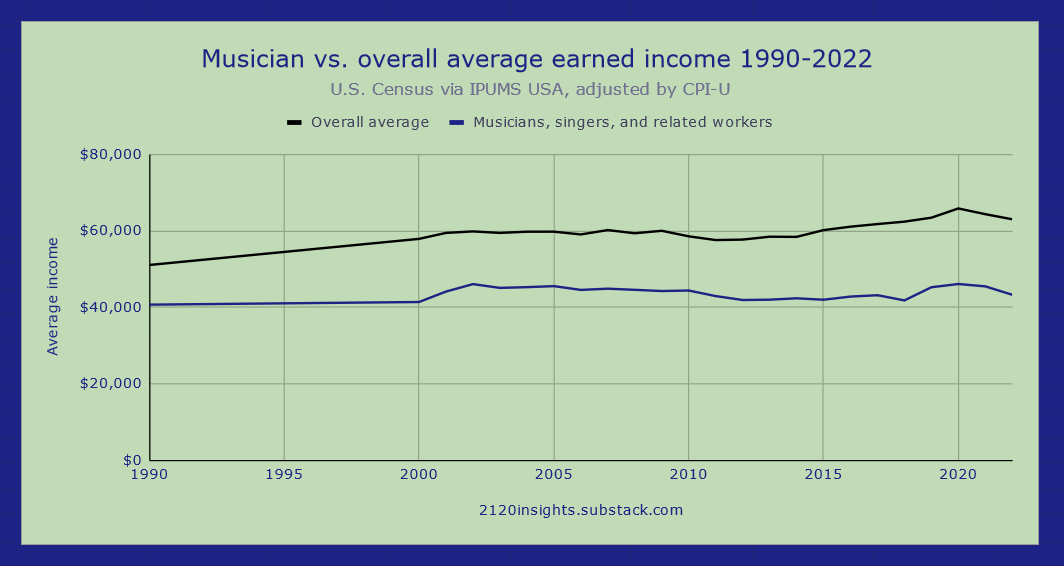

However the average earned income for musicians has barely moved up at all since 1990 in inflation-adjusted terms, hovering at just over $40k per year ($43k in 2022)3. This stands in contrast to overall average earned income which has grown from $51k to $63k.

That said, it’s interesting to compare how many musicians there are against other creatives. In 2009 there were almost equal numbers of musicians, visual artists4, photographers/videographers, and authors. But all of these other occupations grew faster in the following years.

Given the development of the internet and social media over the 2010s, it’s not surprising to see growth in Etsy creators, Youtubers, and bloggers outpacing musicians. But with people starting to spend gradually less time online for the first time ever, it might be about time for a renaissance of live entertainment. As clever as AI music generators might get, it’s difficult to imagine them replacing the desire for human connection that drives people to see their favorite artists in-person.

P.S. For more thought-provoking reads about music and culture, I highly recommend checking out The Honest Broker by Ted Gioia.

If we estimated that the art, drama, and music teachers that were reclassified in 1970 continued to make up a similar fraction of the workforce (0.21%), we would assume a conservative estimate of about 350,000 of these teachers through the US today. However, the total number of teachers relative to the population has grown about 20% since 1970, so 420,000 might be a good mid-level estimate.

On the high end, the BLS employment projections team estimates there were 123,900 art, drama, and music teachers at the post-secondary level alone in 2022 (which only employs 15.5% of all teachers). If there is a similar proportion of these teachers across all grades, there could be as many as 800,000, well ahead of other commonly cited estimates!

My previous piece on measuring occupational change over time includes a detailed footnote about how to think about these re-definitions.

This figure includes income earned from other jobs outside of music. If we summed up the sources of revenue from 2018 listed in the figure above, we get $16,882, which is just under half of the $35,872 that musicians reported earning in the Census (in nominal terms) on average that year.

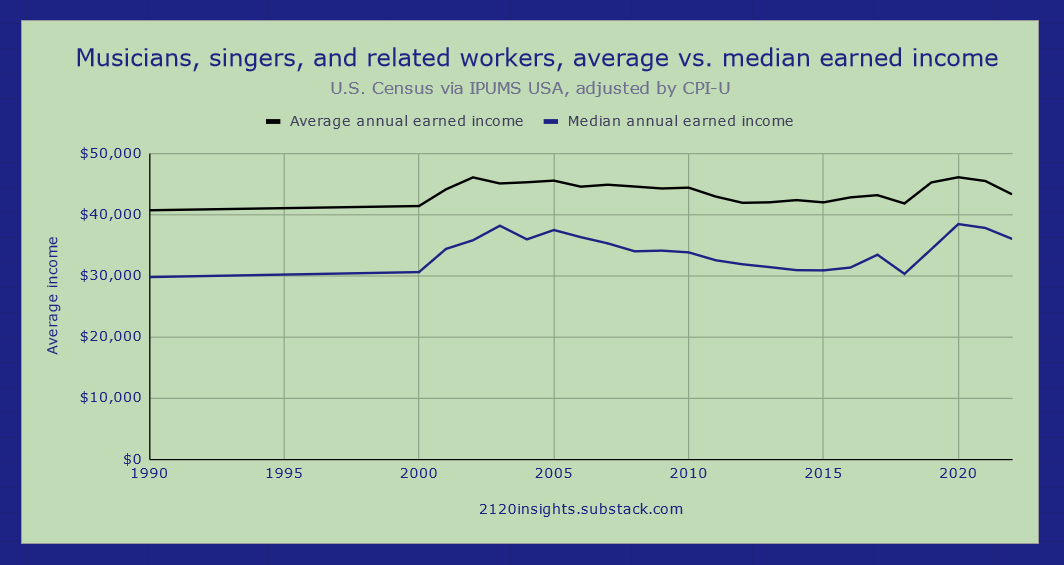

It’s also worth noting that all of the above figures are means. Given how much top artists earn, the average skews a little higher than what the typical (median) musician might earn. Median earned income of musicians was only $36,000 in 2022, over $7k less than the average.

Still, the that gap between average and median is narrowing ever so slightly. This could be reflective of the challenges of making money from digital recording/steaming vs. analog formats. Less revenue from recorded music, and the rise of micro-culture over mass culture could be hitting well-known higher-earning artists more vs. local acts, who have benefited from people generally having more time and money to enjoy live shows.

If you were similarly curious about why there was a significant fall in the number of artists in the 1990s and early 2000s, I came across a few potential explanations:

The automation of some illustration work in animation due to advancements in CGI technology